Published originally November 22, 2006

Midway through Swann’s Way, we find Swann looking at what he thinks is the bedroom window of his lover, the courtesan Odette de Crécy. Earlier in the evening she complained of a headache and declined to make love—to make some “nice little cattleyas”, in Proust’s amusing phrase. Suspecting that Odette sent him away so she could entertain another man, Swann has returned after midnight to spy on her.

Jealousy has reduced him to a peeping tom. No matter. Swann is shameless. Spying outside a window, “bribing servants, listening at doors” are now “merely methods of scientific investigation with a real intellectual value.” Impassioned by “the desire for truth,” Swann knocks on the window shutter. He hears a voice. The window opens. Two old men stand in an unfamiliar bedroom, looking at him questioningly.

This comic moment occurs near the bottom of the parabolic trajectory that characterizes Swann’s love for Odette. Starting in indifference, descending to unrelenting jealousy, and ending several years later once more in indifference, the milestones of Swann’s love are clear. Meeting Odette at the Verdurin salon for the first time, he finds her unattractive, though speculates that others may think her beautiful. When, later, her cheek reminds him of a figure in a Botticelli fresco, Swann develops an aesthetic appreciation of her. Jealousy and obsession soon follow, and with them physical and mental anguish. Only after a prolonged separation does Swann gradually become indifferent again. The story reveals a truth demonstrated throughout In Search of LostTime. To love is a complex experience, and love—indeed all social experience—cannot be contained by a single verb:

For what we believe to be our love, or our jealousy, is not one single passion, continuous and indivisible. They are composed of an infinity of successive lives, of different jealousies, which are ephemeral but by their uninterrupted multitude give the impression of continuity, the illusion of unity.

If we readily understand Swann’s move from indifference to aesthetic appreciation, the leap to crazy-making jealousy is puzzling. Why would Swann, son of a wealthy stockbroker, owner of large estate, at ease in Parisian high society, and quite acquainted with prostitutes, become obsessively, publicly in love with a courtesan?

“Courtesans exist in all times and places….But has there ever been an epoch in which they made the noise and held the place they have usurped in the last few years?” wrote an observer of Parisian society in 1872. “They figured in novels, appeared on stage, reigned in the Bois, at the races, at the theatre, everywhere crowds gathered.” In a study of the emergence of modernism, The Painting of Modern Life, T. J. Clark argues that the courtesan was a category, a way of perceiving (and representing) a changing Parisian culture. She was, Clark writes, “the necessary and concentrated form of Woman, of Desire, of Modernity… ‘the captain of industry of youth and love’.” Captain of industry, but only with a wink of the eye, for “it was part of the myth that the courtisane’s attempt to be one of the ruling class should eventually come to nothing.” The courtesan’s game was “to play at being an honest woman;” her admirers, aware of the game, knew she was not of the ruling class at all but from the “faubourgs or the Parisian lower depths….”

Odette was from the demimonde, the half world, Proust tells us. The term refers to the night world of prostitution and suggests a place in the consciousness of the bourgeoisie where the lower classes are shuffled off, marginalized, and contained. Demimonde also brings to mind the outskirts of the city where the working class was being relocated as Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann remade Paris.

Odette’s play acting causes us sometimes to laugh and other times to cringe as she attempts to be part of high society. Proust calls her a cocotte—hen—a term used for women who had not achieved the highest rank in the world of courtesans (see Virginia Rounding’s study of Parisian courtesans, Grandes Horizontales, for the distinctions). Though Odette succeeds at ruling Swann sexually, she is not convincing in her role as a woman of the ruling class.

Flaubert observed of 1870 Paris, “Everything was false, false army, false politics, false literature, false credit, and even false courtisane’s.” Fourteen years later, Joris-Karl Huysmans would depict in his novel À Rebours a world where falsity itself is the highest virtue. The courtesan’s falsity, her play acting, was quintessential to fin-de-siècle life.

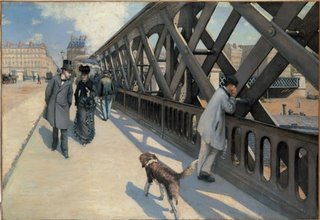

Though the middle and upper classes marginalized the courtesan’s origins, they cast her in a central role as representative of the cultural changes sweeping Paris. In Gustave Caillebotte’s painting, Le pont de l'Europe, our eye, guided by the diagonals of the road, dog and trestle, rests on a courtesan strolling with an upper class gentleman. A worker looking from the bridge ignores them and whatever city life may be happening behind him. The painting captures the courtesan of late 19th-century Paris—class differences, the duality of attraction and disregard, the public spectacle taking place in a Haussmann street clean to the point of sterility.

Odette plays the game, but she isn’t alone. The Verdurins and nearly every member of their salon exude falseness. And Swann himself is characterized by a kind of falsity. The narrator of the first section of Swann’s Way remarks: “It appeared that [Swann] dared not have an opinion and was at ease only when he could with meticulous accuracy offer some precise piece of information.” Swann has strong opinions about what Odette should or should not do, and changes them as his needs require, but he rarely ventures an opinion we feel is not determined by his obsessive love. Swann takes a stand for the first time when he laughs off the Verdurin’s disparaging remarks about his society acquaintances. Swann’s honesty contributes to his expulsion from the Verdurin salon. Falsity is woven into the fabric of Parisian high society.

When indifference to Odette returns, Swann is drawn to Combray. The worlds of Paris and Combray are not neatly separated. Combray has its fake, the snob M. Legrandin. His sister, Mme. de Cambremer, has married into Parisian aristocracy and is returning to Combray for a visit. But the village’s two ways—Swann’s and Guermantes—balance each other, and, one feels, the village itself.

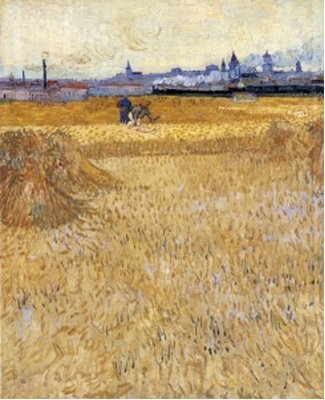

As in Van Gogh’s The Mowers, Arles in the Background, with its figures working together to gather a plentiful harvest, its steepled church, and a village that seems to embrace the train that races by, life in Combray is of a piece. Swann is anxious to get back.

As in Van Gogh’s The Mowers, Arles in the Background, with its figures working together to gather a plentiful harvest, its steepled church, and a village that seems to embrace the train that races by, life in Combray is of a piece. Swann is anxious to get back.

5 comments:

I have a question: why does Swann eventually marry Odette?

Reading your post makes me think that maybe the same 'intellectual laziness' that Proust describes in him several times, leads him to this. He slips into love with her through a kind of carelessness, a jumbling together of different impressions. The Vinteuil piece makes him think of love, Odette, who plays out attraction to him, becomes associated with the piece, suddenly he is in love with Odette.

Does the same thing lead him to marry her?

I'm goin' nuts! Please relieve my distress. I've read the first three chapters of Swann's Way, and just finished Swann in Love. In early chapters, it's quite clear that Swann eventually marries Odette, and they have a child, Gilberte, who is about seven years old.

Swann in Love was really fascinating, full of nuance, surprise, irony and psychology. Proust was an acute observer of human psychology. Throughout Swann in Love, I kept wondering how, when, and why he would marry Odette, and how the two would feel about it. As I saw I was getting near the end of the story, I became increasingly anxious. How would Proust wrap it up? To my shock and horror, he doesn't wrap it up. At the end of Swann in Love, Swann has lost interest in Odette and regrets the time he wasted loving a woman who clearly was not right for him.

This seems like a dirty trick by Proust, though it might be intended to keep his readers interested, through the remaining six volumes, hoping to find out.

Toward the end of Swann's Way, late in the fourth chapter, Odette is described by former customers and lovers as Mme. Swann. So it seems pretty clear that something happened.

Please, please, please, throw me a few clues.

Tim

He never tells you. I'd be interested to know whether it is because he overlooked it, he died before he got to write it or else he felt he had said enough already.

Hi dotdave.

No hints anywhere in all seven volumes? I'll go crazy!

He didn't run out of time and then die. I think the seven books were written approximately in chronological order. He didn't overlook it. He was a compulsive re-writer. The omission seems quite deliberate.

I imagine scholarly essays and doctoral dissertations have investigated the question of how Swann and Odette got together, and why Proust left it up the the reader's imagination. I'd like to read more on the topic, but don't know where to look.

How does the chronology work out? We know Gilberte's age. Does Odette have the baby while away at sea, or does she get pregnant after she returns, after Swann has lost interest in her? Later on, Swann seems fond of Gilberte, so it seems reasonable to suppose that he is her father.

Did Swann marry Odette and give her a child out of some friendly sympathy, after she discloses all, repents, and wishes for a happier and more conventional life? Is this echoed by Swann's polite conversation with the young prostitute in the house of ill repute, near the end of the chapter?

Cheers,

SB

Don't forget Proust wrote this over a long period of time during which he changed course more than once. Also, when you get to the last volume, you will notice there are some errors which he did not have time to correct before he died. So it is entirely possible that at one time he intended to give a more detailed explanation of the marriage and then either changed his mind or never got back to it.

I think a lot about the two 'ways' (Swann's and the Guermantes') and so I wonder whether marrying Odette was one manifestation of Swann's way, a way which included considerable compromise and lack of belief. Think about the way he highlights Swann's tendency to put quotes, as it were, around anything he says that smacks of a firm opinion.

Swann's rise into aristocratic society makes him a man of the world, a man who ceases to believe things deeply, although when you get to the passages about the Dreyfuss affair, you will see he changes a bit, but this is late in his life.

He has ceased to believe in much of anything and falls into a relationship with Odette very much against his will and by accident.

We do get some hints as to whether Gilberte is really his daughter, but they are oblique and they happen after Swann has died when we observe how she conducts herself in terms of her relationship to him, in particular utterly denying that she is, as a result, half Jewish. Perhaps this is because she is not in fact half-Jewish but simply a child raised in part by a Jewish man who happened to be married to her mother.

One other possibility I sometimes wonder about: did Swann marry Odette as a favour after she became pregnant by some other man? You get hints of a kind of messy, hidden nobility in Swann from time to time and at those moments, this thought has occurred to me.

On the whole, it is left mysterious. We are as mystified by it as the characters in the novel. How true that rings: do we ever really know why people do the things they do?

Post a Comment